London’s black cab drivers don’t just memorise a few shortcuts. To earn their licence, they sit “The Knowledge” - a grueling exam that demands mastery of 25,000 streets, landmarks and routes. It can take years. MRI scans show that as they train, their hippocampi - the part of the brain tied to spatial memory - literally bulk up. Like a bicep curling iron, the brain grows with repeated effort.

But when the work stops, so do the gains. Studies on retired drivers suggest the hippocampus shrinks back - a reminder of “use it or lose it.” Neuroplasticity cuts both ways: the brain strengthens the pathways we use and prunes those we don’t. Muscles waste without training and so do neural circuits. But with GPS everywhere, do we really need to keep building that (hippocampus) muscle? Perhaps outsourcing spatial memory to Uber or to future robotaxis is simply rational.

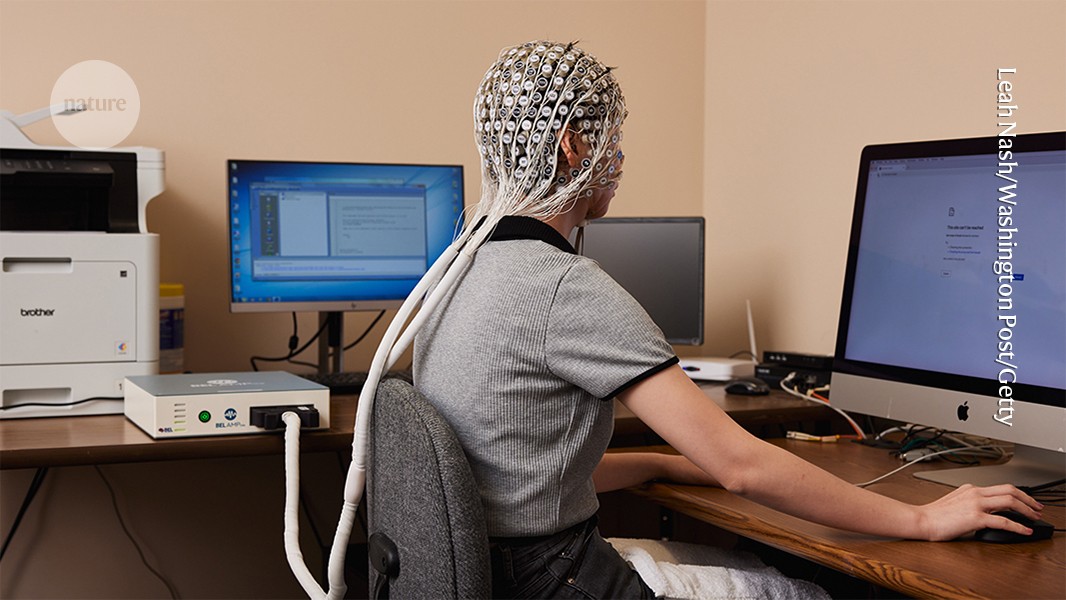

Now place that image beside a new study from MIT Media Lab. Instead of maps, the task was essay writing. Instead of street knowledge, the tool was ChatGPT. The researchers found that people who leaned on the AI showed less neural engagement. Their brains weren’t firing in the same way. The essays looked polished, yes, but the cognitive sweat was missing. And when those AI-reliant participants had to write without assistance later, their brains stayed in low gear - as if the mental muscles had forgotten how to push.

This is the quiet danger of AI, its not the flashy hallucinations or obvious biases, but the erosion of effort. You don’t notice shrinkage in real time, any more than a driver feels their hippocampus wasting away. A little less recall here, a little less critical effort there. The atrophy happens quietly, invisibly.

We have seen this before. GPS made navigation effortless but chipped away at our internal maps. Search engines gave us infinite information but also the “Google effect” - we remember less of the facts themselves, more of where to find them. When something so convenient arrives, the load on our brains naturally gets lighter such that maybe the very structure of the brain starts to change and cognitive strain shows up less in the scans. But isn’t that the point of technology, to lighten daily life? Strain may be uncomfortable, but it’s often what makes us stronger.

That’s where the gym metaphor bites. Thof ChatGPT in context of new fitness programme. You can use it like a protein shake - fuel that amplifies the hard reps you’re already doing. Or you can treat it like a hired lifter doing the bench press while you nod along. The first path makes you stronger. The second might make you feel good but leaves you hollow underneath.

Some groups are more exposed. Children and teenagers, with still-forming brains, may be at particular risk. The shortcuts of ChatGPT don’t just shape homework and essays only, they shape how young people learn, socialise, even seek comfort. A U.S. lawsuit alleges the tool played a role in a teenager’s suicide, while 44 state Attorneys General warn of chatbots flirting with minors or encouraging harm. If black cab training can bulk up an adult hippocampus, what happens when adolescents outsource whole categories of thinking and relating to machines?

That’s why the responsibility isn’t just personal. Thoughtful use has to spread into classrooms, parenting and policy. If AI is the fitness programme for our brains, some walk in with decades of training while others are lifting for the first time. The risks and the responsibilities are uneven.

We won’t have longitudinal studies for years. By the time the data arrives, the habits will already be cemented. But here’s the harder truth: the ramifications aren’t the same for everyone. A seasoned professional leaning on AI for speed isn’t in the same position as a teenager shaping their first sense of self or a child learning how to think before they’ve even built the cognitive muscles.

For parents and educators, that responsibility is especially sharp: children don’t get to choose their training plans. Guiding how they use these tools may be as important as teaching them to read, write and navigate the world.

So the question isn’t just whether you’ll treat AI as scaffolding or substitution - it’s whether we’ll make scaffolding the default, before the quiet atrophy sets in where it hurts most.